[The cataloguing project Musikalische Quellen (9.-15. Jahrhundert) in der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek (Musical Sources (9th-15th Century) in the Austrian National Library), conducted by Alexander Rausch and Robert Klugseder at the Austrian Academy of Sciences, has made the Linz Fragments available online in high-resolution images. All links to the source including a preliminary inventory by Reinhard Strohm go to the homepage of this project. The image rights lie with Robert Klugseder who took the photos.]

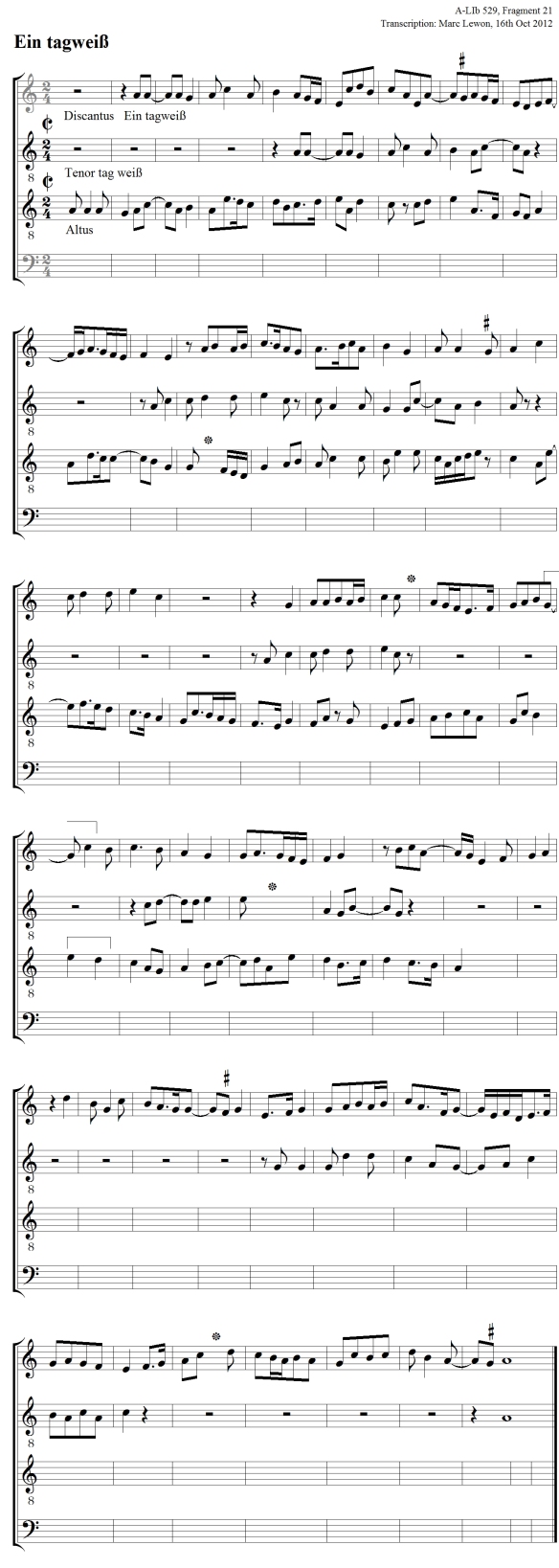

Ein tagweiß

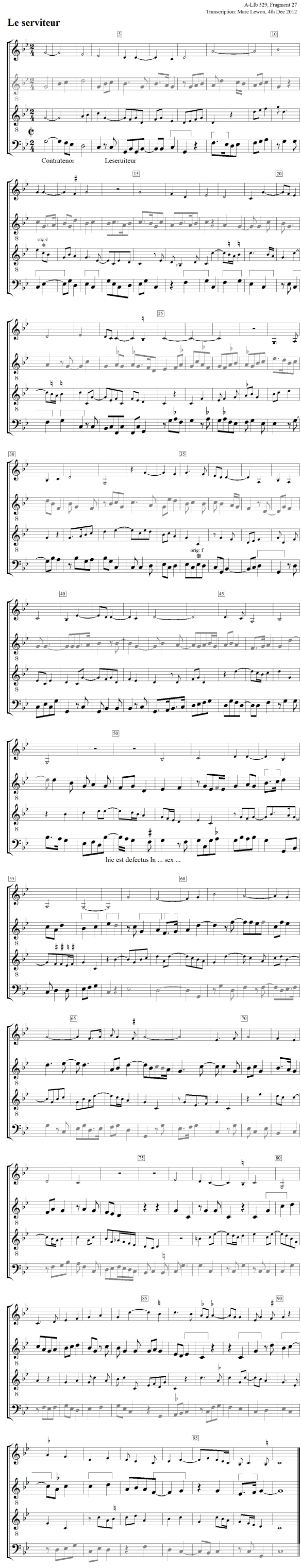

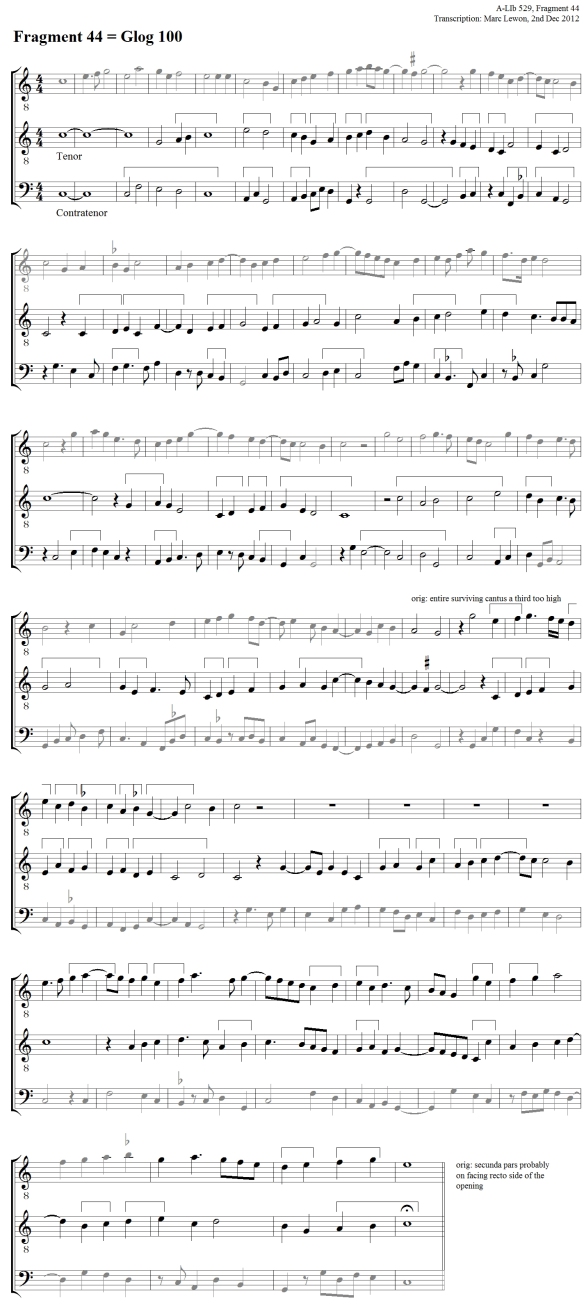

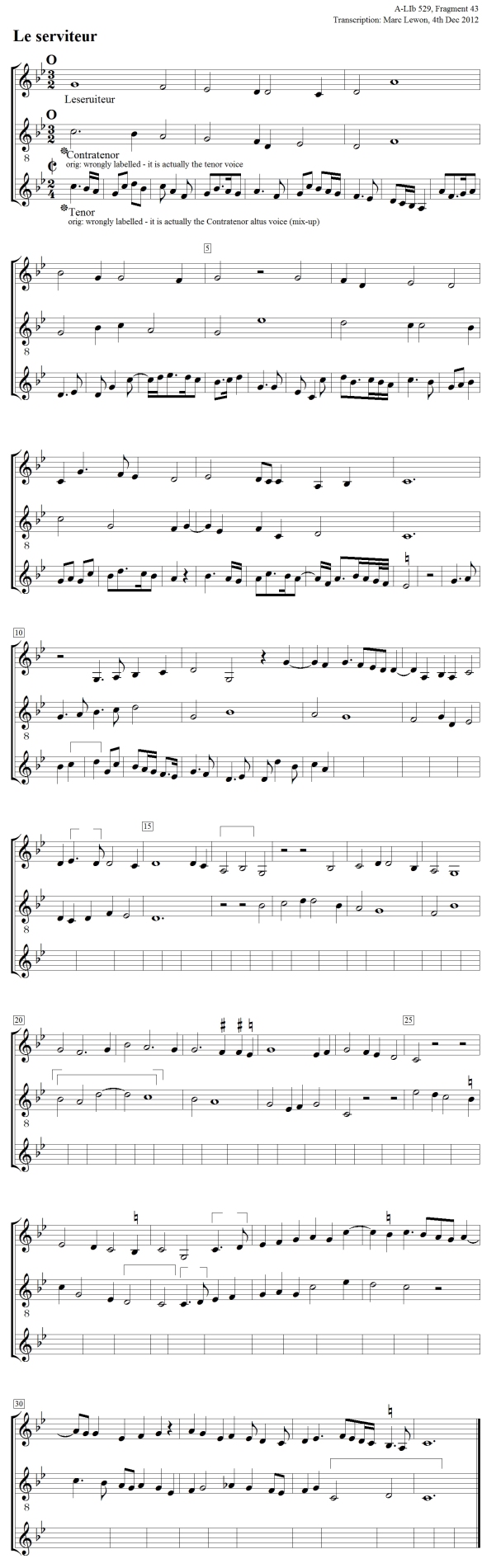

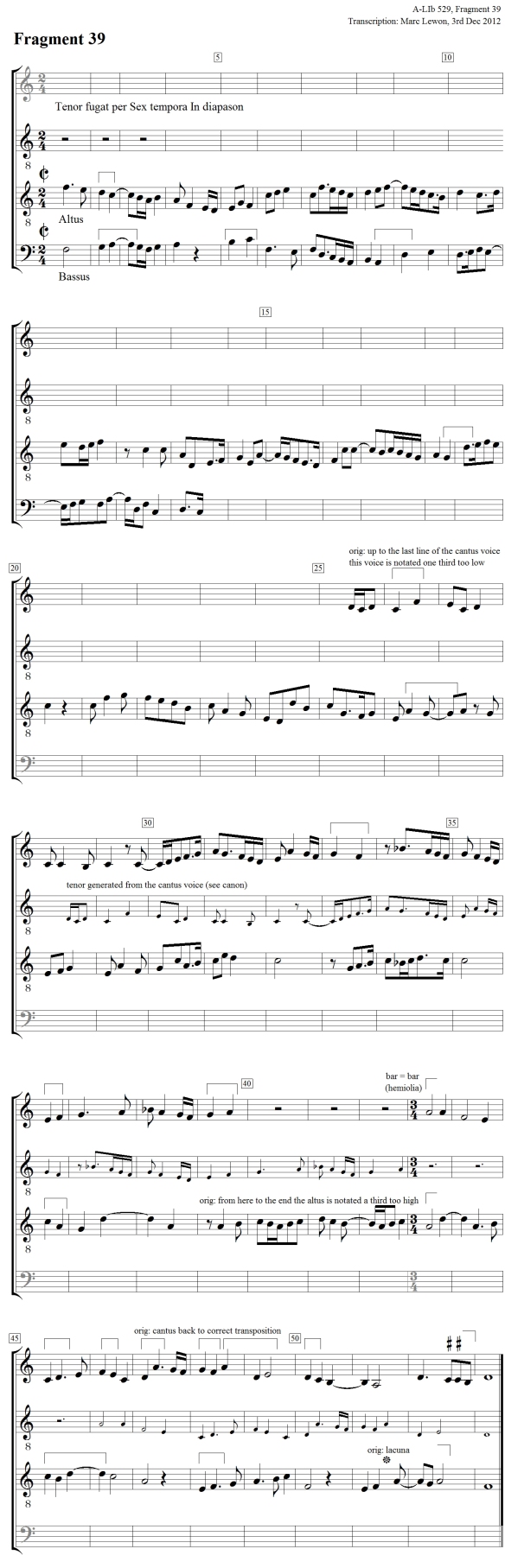

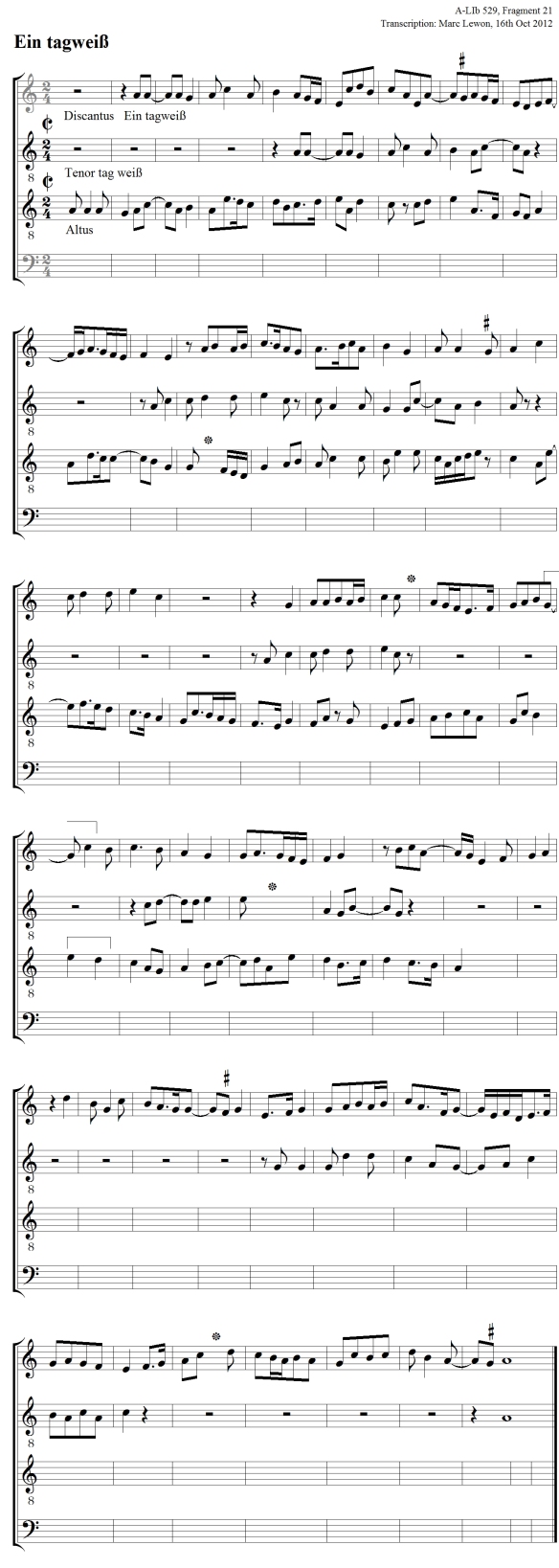

Reinhard Strohm’s preliminary inventory features yet another very interesting title on Linz Fragment 21 (which constitutes the reverse side of the folio containing Fragment 20 with “stúckl”, see last entry): “Ein tagweiß”. The title sparks associations to the genre of “Tagelied” from the minnesang tradition. Even though the piece is transmitted textless here, it can be assumed that the tenor line, which apparently presents the cantus firmus, once was connected with a text containing typical Tagelied motifs (such as the approaching dawn, the call of the watchman, the farewell of secret lovers, etc.). Unfortunately, yet again the notation remains fragmentary: Only cantus and tenor present an almost complete duo, while the altus voice breaks off about two-thirds into the piece and the bassus is missing altogether. The surviving parts, however, give a good impression of what the composition was about: a great deal of imitation and an interesting rhythmical structure. (And it would not be difficult to add some very obvious imitations by the bassus voice.)

The following edition follows the original time signature of imperfectum diminutum, but presents a slightly misleading visual impression: The most obvious rhythmical structure, which becomes immediately noticeable when glancing at the original and which Reinhard Strohm described as a “strikingly repetitive, ‘modal’ rhythm”, is obscured in the modern edition. It seems to call for a performance in an imperfectum maior prolation, starting with an upbeat. Each time after a melodic motif has been imitated, however, the rhythmical structure changes into an even measure towards the ensuing cadence. Only the tenor line remains entirely in the “first rhythmic mode”, indicating that the melody of the original song was completely rhythmised in this fashion. Many monophonic melodies of the 15th century feature this kind of simple rhythmic structure, which I like to call “reference rhythm” (for more information on this rhythmic principle and its consequences, see: Marc Lewon: “Vom Tanz im Lied zum Tanzlied? Zur Frage nach dem musikalischen Rhythmus in den Liedern Neidharts“, in: Das mittelalterliche Tanzlied (1100-1300). Lieder zum Tanz – Tanz im Lied, ed. Dorothea Klein with Brigitte Burrichter and Andreas Haug, Würzburg 2012 (= Würzburger Beiträge zur deutschen Philologie, vol. 37), pp. 137-179, esp. pp. 169-176 and „Das Lochamer-Liederbuch in neuer Übertragung und mit ausführlichem Kommentar“, ed. Marc Lewon, 3 vols., Brensbach 2007-2010, vol. 2, p. 35, 37 and 46).

Four little lacunas, which occurred due to the cropping of the page and apparently led to the loss of only a small amount of notation, are marked with an asterisk.

“Ein tagweiß”, missing notation left blank.

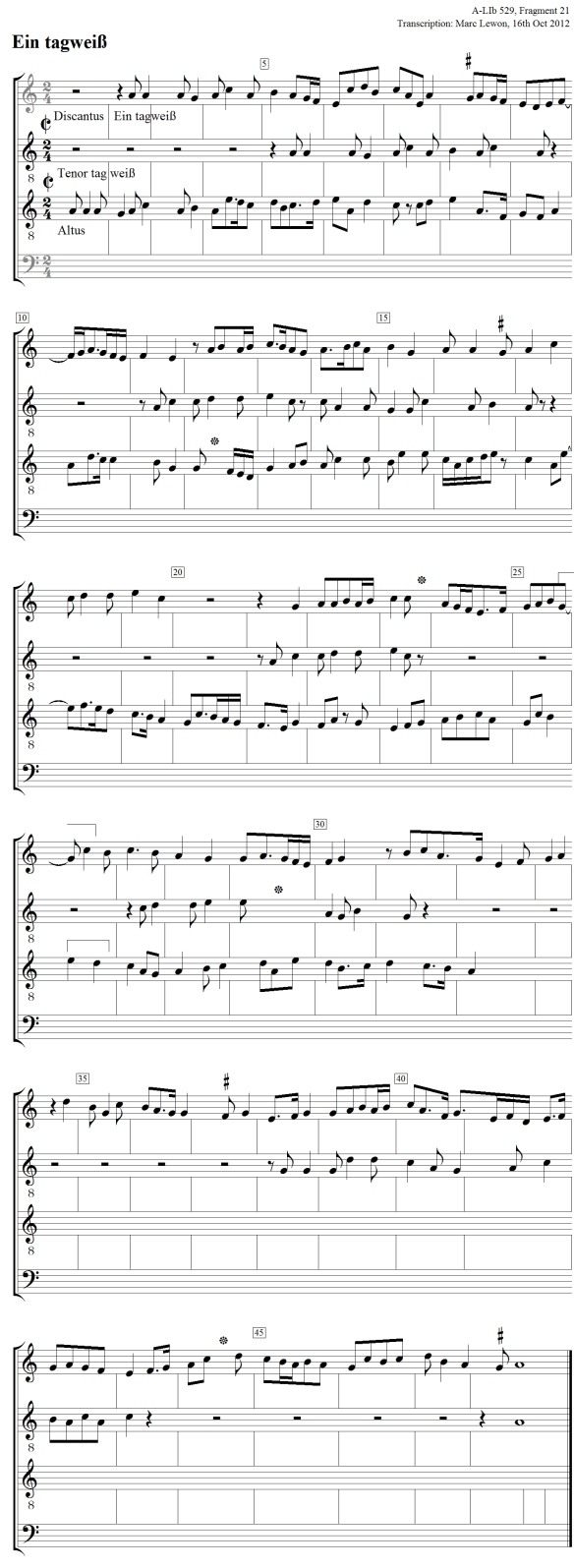

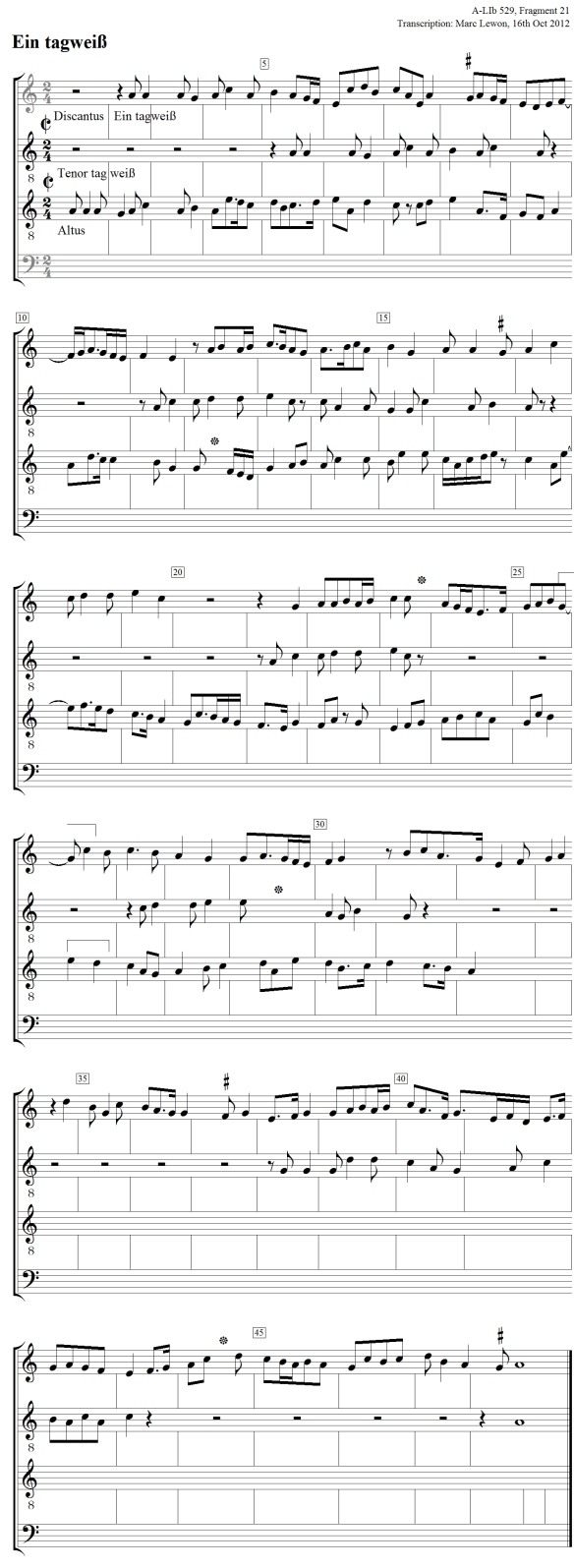

It is obvious that especially for this piece the use of mensuration lines is to be preferred in a transcription in order to give a better representation of the “hidden” rhythmical structure:

“Ein tagweiß”, missing notation left blank, edition with mensuration lines

PS: This fragment is now also posted on “Marc’s Milk Carton” as one of “Marc’s Most Wanted”: Check out the reconstruction of the monody behind this composition—maybe someone can recognise and identify the piece.

Marc Lewon

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.